The Alchemy of Invented Lack

In the vast, scrolling expanse of the digital marketplace, a peculiar and potent form of alchemy occurs: the transformation of contentment into lack. Content titled “Amazon Kitchen Accessories You Didn’t Know You Needed… Until Now | Mind = Blown.” is the master text of this alchemical process. It does not sell solutions to expressed needs; it sells the need itself, wrapped in the thrilling package of discovery. The “mind-blown” reaction is not to the object’s function, but to the sudden, destabilizing realization that one’s life has been secretly, subtly deficient.

This genre operates on a more sophisticated level than simple impulse marketing. It engages in a form of retroactive problem-creation. It identifies a micro-friction in daily life—an action so habitual and minor we’ve ceased to register it as friction at all—and through the lens of a new gadget, magnifies it into a glaring inefficiency. The “aha!” moment is not joy at a solution, but manufactured shame at one’s previous ignorance. This review will dissect this psychological operation. How does an object move from non-existent to “essential”? What narrative techniques convert minor convenience into revolutionary necessity? And what are the personal and cultural consequences of living in a state of perpetual, market-driven revelation about our own domestic inadequacy? We explore the gap between a “blown mind” and a wiser one.

2. Deconstructing the “Didn’t Know You Needed” Paradigm

This phrase is the genre’s foundational rhetoric, a clever linguistic trick that disarms skepticism and primes the viewer for conversion.

A. Pathologizing Contentment: To state that someone “didn’t know they needed” something is to imply that their previous state of non-need was a form of ignorance or naivete. Their satisfaction was not authentic; it was a lack of awareness. The product becomes a corrective to a flawed perception, positioning the buyer on a higher plane of consciousness. You weren’t happy before; you were just uninformed.

B. The Colonization of the Mundane: These products target the utterly banal, uneventful corners of kitchen labor: spreading butter, peeling garlic, cracking eggs, storing a half-used onion. By focusing here, the genre suggests that no aspect of domestic life is beyond optimization, that there is no natural, acceptable level of minor inefficiency. It turns the entire kitchen into a site of potential problem-solving, and thus, potential consumption.

C. The “Revelation” as a Social Currency: The “mind = blown” formulation frames the discovery as a shareable epiphany. It’s not just a purchase; it’s an entry into a club of enlightened individuals who have seen the light. Sharing the product or the video becomes an act of proselytization—”Look what you’ve been missing!” This creates a powerful viral loop where the act of being persuaded becomes the act of persuading others.

D. The Illusion of Agency: Crucially, the genre presents this “need” as something the viewer discovers for themselves in a moment of personal revelation. This masks the highly engineered nature of the persuasion. The marketer’s hand is hidden; the need feels organic, self-generated. This makes resistance feel not like sensible consumer caution, but like a stubborn refusal to embrace a personal truth.

3. Taxonomy of the “Mind-Blowing” Accessory

The products that succeed in this genre are not merely useful; they are theatrically useful. Their value is demonstrated in a miniature drama of before-and-after transformation.

Category 1: The “Elegant Bypass” Gadget

These items circumvent a simple manual skill with a Rube Goldberg-esque mechanical solution.

-

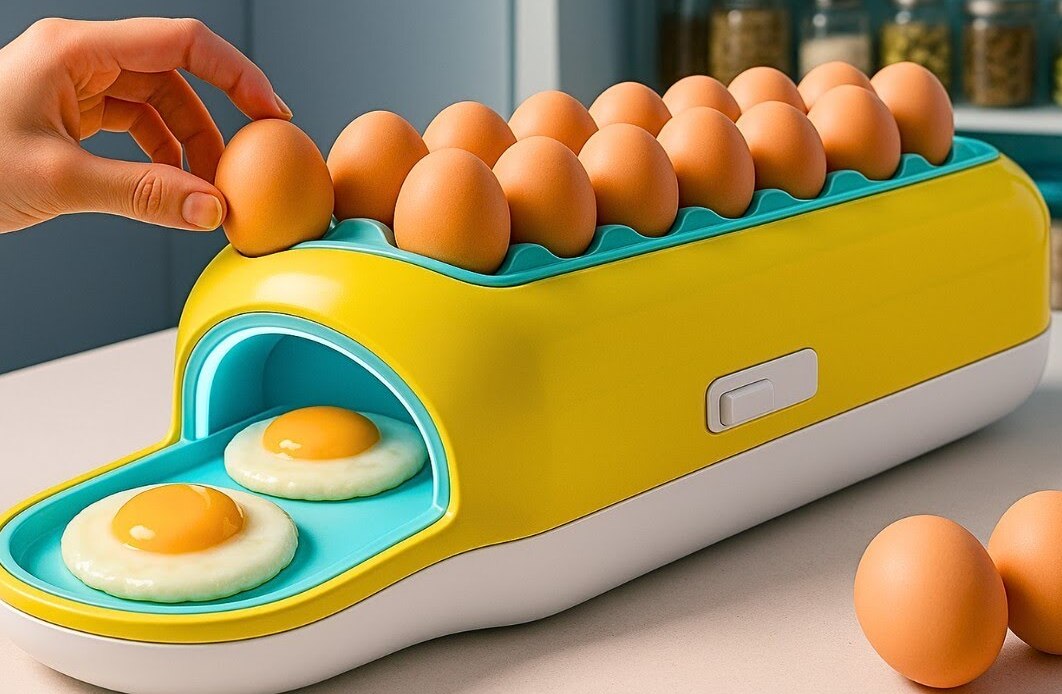

Examples: Manual egg crackers that separate shell from white in one press; avocado slicer/pitter tools; strawberry hullers with a claw mechanism; banana slicers that cut a whole banana into perfect discs at once.

-

The “Mind-Blown” Mechanism: The drama lies in watching a multi-step, slightly messy manual process (cut, twist, pry) become a single, clean, mechanical action. The “blown mind” is a reaction to unnecessary engineering. The critical flaw is that these gadgets often take longer to clean than the time saved, and they perform a task already easily accomplished with a knife—the ultimate multi-tool they aim to replace.

Category 2: The “Hyper-Specific Salvager”

These accessories promise to rescue value from waste or failure, appealing to both frugality and perfectionism.

-

Examples: “No-waste” citrus reamers that get every last drop; jar spatulas to scoop out the final remains of peanut butter; egg yolk separators that guarantee no white in your yolk; herb strippers that pluck leaves from stems in one motion.

-

The “Mind-Blown” Mechanism: The revelation is that you have been passively accepting waste or imperfection. The gadget positions you as a master of efficiency, leaving nothing on the table. It monetizes the anxiety of waste and the pursuit of culinary purity, often for gains measured in teaspoons and pennies.

Category 3: The “Spatial Illusionist”

These items create order or functionality from perceived chaos or wasted space through clever folding, nesting, or multi-use design.

-

Examples: Collapsible silicone colanders that fold flat; measuring cups that stack into one; pot lids that double as strainers; multi-tiered, expandable dish drying racks.

-

The “Mind-Blown” Mechanism: The “blown mind” is a spatial one: “I can’t believe it fits there!” or “It’s four things in one!” The drama is in the transformation, the magical compression or expansion. The trade-off is often sturdiness, durability, or ease of use; the complex mechanism that enables the trick is often the first point of failure.

Category 4: The “Ergonomic Overcorrector”

These tools address a physical discomfort so minor most people have never identified it as a “problem.”

-

Examples: “Comfort-grip” peelers or can openers, angled measuring cups you can read from above, “no-slip” silicone cutting boards, jar openers for “weak hands.”

-

The “Mind-Blown” Mechanism: This one works through retroactive identification of pain. The viewer sees the tool and thinks, “You know, my hand does cramp when I peel potatoes…” It manufactures a somatic memory of discomfort to justify the purchase. It’s a solution that creates its own problem in the buyer’s mind.

4. The Consequences of Perpetual Revelation

The constant drumbeat of “things you didn’t know you needed” cultivates a specific and problematic mindset.

A. The De-Skilling of the Domestic Cook: When a new gadget emerges for every micro-task, the foundational skill of using a sharp knife confidently atrophies. Why learn to chiffonade herbs when a “herb chopper” exists? The kitchen becomes a suite of single-use automations, and the cook becomes a manager of gadgets rather than a practitioner of a craft. The true “mind-blowing” skill—competence with a core set of tools—is forever deferred.

B. The Clutter of Solved Non-Problems: Each purchased solution to a manufactured need takes up physical and cognitive space. The drawer becomes a museum of abandoned revelations—the egg slicer used twice, the avocado tool relegated to the back. The quest for a simplified life through gadgets results in a profoundly complicated one.

C. The Economic of the Infinite Micro-Transaction: While each item is often cheap (the “under $20!” tag is common), the collective cost of continually discovering new “needs” is substantial. It’s a financial death by a thousand cuts, where the budget is slowly consumed by an endless parade of trivial optimizations.

D. The Erosion of Contentment: This genre’s most pernicious effect is its assault on satisfaction. It teaches that contentment is a form of blindness, that to be happy with your current tools is to be asleep. It fosters a restless, anxious domesticity where peace is always one more Amazon delivery away. The “blown mind” is quickly followed by the question: “What else don’t I know I need?”

5. Cultivating Immunity to Manufactured Need

Resisting this cycle requires a conscious re-framing of what constitutes a genuine need.

-

The “Friction Journal” Test: Before accepting an advertised “need,” keep a literal or mental log for a week. Note moments of genuine, repeated frustration. Is it struggling with jar lids daily, or once a month? If a friction point doesn’t appear organically and frequently in your own life, it’s not your need; it’s a marketer’s invention.

-

The “Skill vs. Gadget” Evaluation: For any proposed tool, ask: Could I achieve this result with a minor improvement in skill using a core tool I already own? Often, five minutes of practice with a knife yields better, faster, and cleaner results than a new unitasker. Invest in knowledge before hardware.

-

The “Full Lifecycle” Consideration: Factor in the entire cost: purchase price, storage space, cleaning time, and eventual disposal. A $12 gadget that saves 10 seconds but requires 60 seconds to disassemble and clean, and will break in a year, is a net negative.

-

Embrace the “Good Enough” Principle: Accept that some minor inefficiency is the natural tax of a human-scaled life. The 30 seconds of extra effort to mince garlic by hand is not a crisis to be solved; it is part of the rhythm and ritual of cooking. Not every friction requires a productized solution.

-

Practice “Need-Fasting”: Periodically, impose a moratorium on buying any new kitchen item for 3-6 months. This reset period forces you to creatively use what you have, reveals what you truly miss, and breaks the addictive cycle of seeing every micro-annoyance as a retail opportunity.

6. Conclusion: The Unexamined Need is Not Worth Having

“Amazon Kitchen Accessories You Didn’t Know You Needed… Until Now | Mind = Blown.” is perhaps the purest expression of 21st-century consumer ideology. It brilliantly inverts the traditional model of identifying a problem and seeking a solution. Instead, it offers the solution as a dazzling spectacle, and in doing so, conjures the problem into existence in the viewer’s mind.

The true “mind-blowing” realization is not that a gadget can core a strawberry, but that we have become so susceptible to the suggestion that our unhappiness is hiding in the un-cored strawberry. The most radical act in the modern kitchen may be to declare a moratorium on revelation, to find profundity not in the new and the clever, but in the mastery of the simple and the old.

A kitchen liberated from manufactured need is a kitchen of intention. It is a space where tools are chosen for proven utility and endurance, not for the momentary thrill of a solved non-problem. In such a kitchen, the mind is not “blown” by a plastic contraption, but quietly expanded by the growing competence of its owner. The greatest discovery is not the thing you didn’t know you needed, but the deep and sufficient satisfaction found in the tools—and the life—you already have.